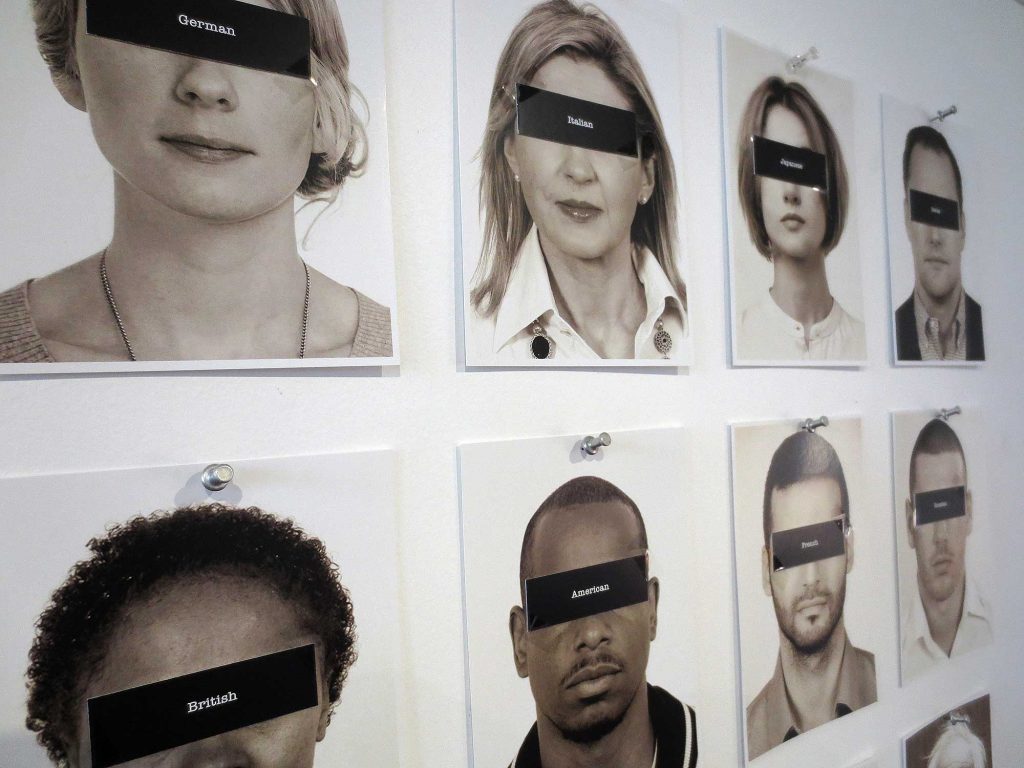

Personal – National

installation, 2019, black and white photographs, push pins, filing cabinets

When we meet a stranger, or generally somebody who seems different due to how they speak, look, dress, and behave, etc., the usual question we ask them is “Where are you from?” assuming they are not from here. We tend to organise this ‘somewhere else’ by means of national countries. We might further ask “What’s your name?” and, if we feel particularly inquisitive, will finish with “What do you do?” Then our verbal inquisition generally tends to end and we move on. What if instead of eliciting a national label as a response to our type of question we asked them about where they are local, well, that would suddenly open up vast possibilities of finding out about the actual person and their human reality.

The way we speak may say something about our background, but it is not key in identifying where we belong, or are ‘a local’. This is particularly true for people who have moved across greater distances during the course of their lives.

The national state is a relatively modern concept and was only constructed in recent times and as a response to the then common concept of monarchy. People like Emanuel Kant had great hopes that the establishment of a national state would end all war as the people would feel responsible and personally committed (and affected) by all that the state did, as they themselves would be the ones doing it and the ones being affected by what they did – unlike a king who orders war but does not fight himself. Sadly Kant was wrong.

The idea of nationality as a means to describe a person is extremely limited. Besides, not all people in one country are really the same. They might share certain traits based on a shared language and resulting common outlook on the world. And many languages spread beyond the confines of national borders, for example English or Spanish or German and spoken across many countries. It would probably be more apt to ask someone which cultural-linguistic lens they use to view the world, if we wanted to find out anything meaningful at all. However author Tayie Selasi, who lives in New York, with parents from Ghana, and who has lived in many other parts of the world, in her TED talk suggests the idea of asking where someone is a local rather than where they’re from as a means to enable a connection between people. Taiye Seals describes herself as a “local” of Accra, Berlin, New York and Rome.

In this installation, 16 portrait photos with emotionless expression like on passport photos are pinned to the wall. The artist deliberately chose faces of people he has never met nor has any personal connection to. The faces are obscured by black pieces of card which are scotch-taped across their eyes. Each piece of card bears a national label. We can sense their eyes but just can’t see them. Drawers in two old metal filing cabinets below the black and white portraits feature corresponding national labels The portraits are organised in rows of four, with the top row representing the countries of the ‘Axis’ of World War 2, plus the financially powerful Switzerland. The remaining 4 rows represent the ‘Allies’, plus countries involved in the Pacific War (as part of WW2). Turkey features as a representation of the military conflicts by the same main participants during WW1. On top of the smaller filing cabinet, in the corner, sits a tape dispenser with an empty roll, and next to it a forgotten label which says ‘human’. The black and white photographs, and overall the antiquated quality of the materials employed, allude to the fact that the concept of nationalism clearly belongs to the past.

National labels and thinking in national concepts bears great risks and allows for concepts like friend and foe, allies and enemies. The national idea brings with it national interests, and is a key factor in making conflict possible on a grandiose scale, i.e. entire countries and peoples going to war with each other. National thinking is a significant aid in the removal of the human element, the personal reality of any experience. This supports black and white thinking, and lies at the root of concepts like national heroism, and national war effort. By focussing on the human element instead, and the human reality of a person we meet, we are able to become curious about their personal experience, which automatically removes the separating quality of national concepts.