Through the Eyes of Angels

Through the Eyes of Angels | Beyond Borders and Patriotism – The Human Dimension of Military Conflict

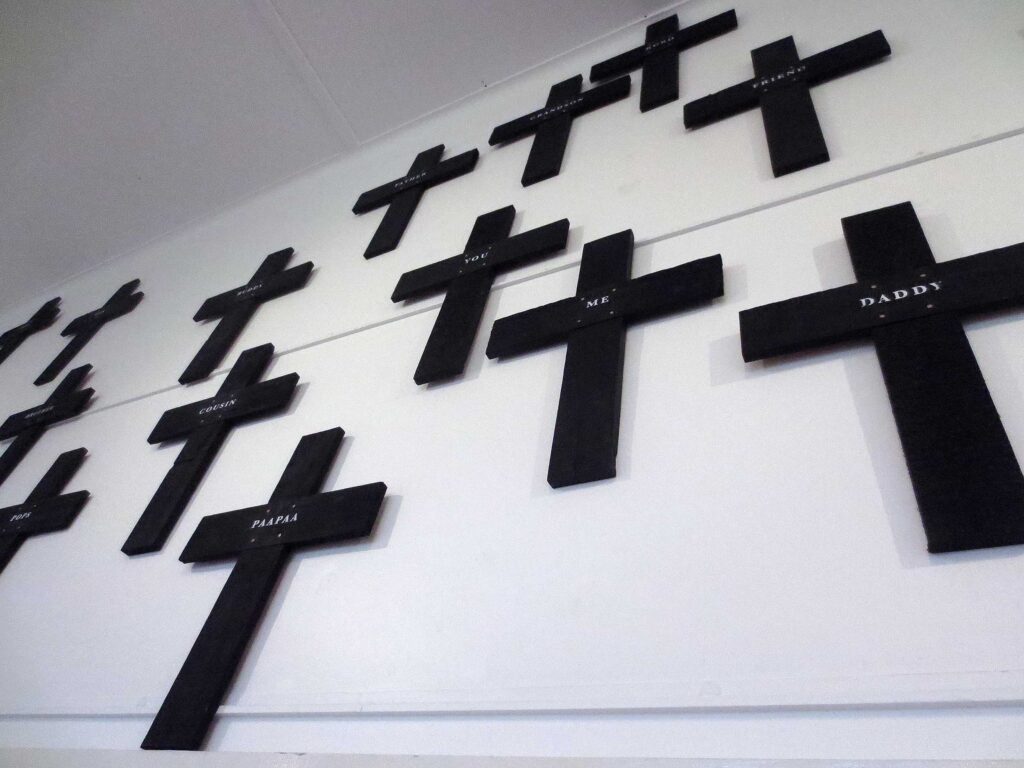

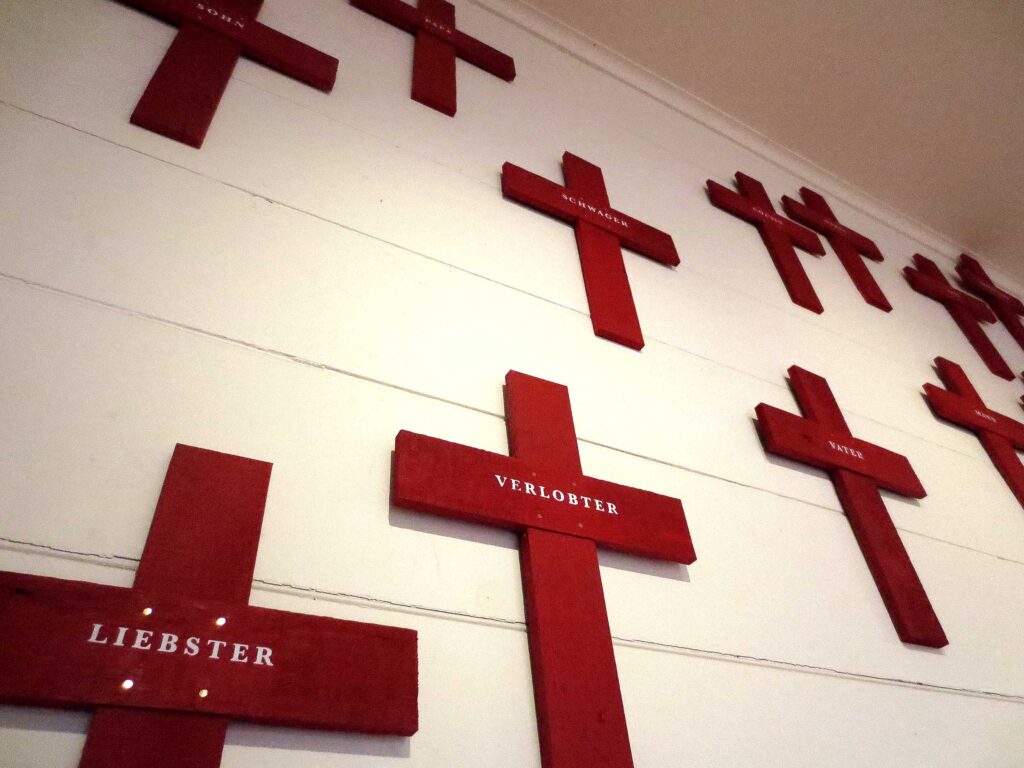

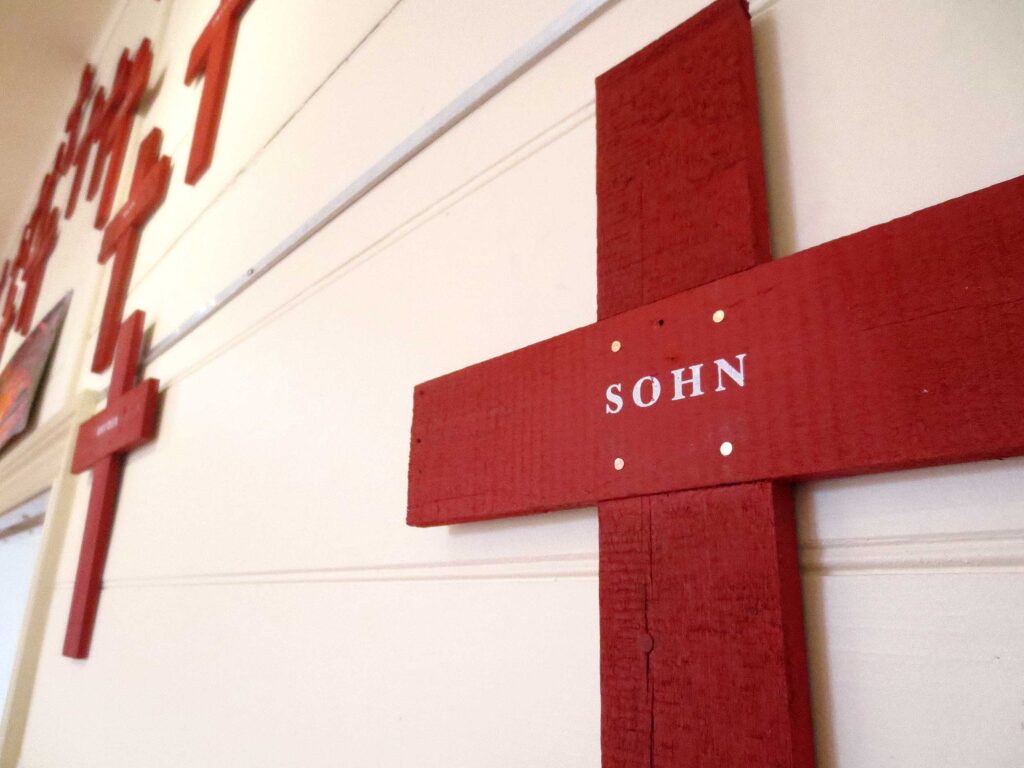

2021 Daniel Kirsch, screen print on painted historic kauri sarking, copper nails, 66 crosses (2 groups of 33)

It’s just hell here now no water or tucker only 7 out of 31 in no. 1 troop on duty not either dead or wound(ed). Darn the place no good writing any more. (From the diary of Alfred Cameron*)

“Two concepts dominate the interpretation of WW1 – on one hand it is viewed as the first “total war” in modern history. In addition to the fighting at the military fronts, for the first time entire societies were mobilised on the “home front” as well, in order to enable an industrialised war between peoples and countries. This war’s pervasive nature affected all of those societies.

According to the other concept, WW1 can also be interpreted as a ‘civilization crisis’ of modern Europe. At the time the war was labeled “The Great War for Civilization” (back of the British version of the Allied Victory Medal 1914-1919) and was touted to be “the war that ends all wars” (H.G. Wells). However, despite this optimism it ended up mobilising all of society’s productive powers for the purpose of destruction and annihilation, with over 10 million dead, even more existences destroyed, societies shattered, political order in collapse, and continual military conflict after the end of the war. “(Wolfgang Kruse, Der Erste Weltkrieg)

“Governments like their people to see war as a drama of opposites, good and evil, ‘them’ and ‘us’, victory and defeat. But war is primarily not about victory or defeat but about death and the infliction of death. It represents the total failure of the human spirit.” (Robert Fisk, The Great War for Civilisation).

Kirsch’s work is a stark statement about the futility of war, and unlike the common rhetoric and rituals employed in remembrance and referral to war, this installation offers us a deeper, more gentle view on the subject by focusing on the human dimension.

The installation consists of two groups of 33 wooden crosses each, made of painted rough sawn historic kauri sarking. Instead of the battalion, rank and name of the soldier who died, the crosses name the relationship this person has had to those who are left behind and who mourn him. The two groups of crosses are each arranged in random order on either side of the same wall, which joins the gallery’s two rooms. On entering the gallery the viewer only sees Group 1 (NZ English on black crosses) not knowing there is a second group on the back of the same wall. Only after stepping through the portal in the centre of the wall into the other room of the gallery – and turning around – does the viewer discover the red crosses, which again name the soldiers’ relationships, only this time in German. The two groups on either side of the one wall describe the exact same human reality of war – in two different languages.

While the languages chosen also have personal relevance to the artist, they are part of the dominant languages spoken in WWI (and WWII). Our grandparents and great grandparents may well have been shooting each other, and creating the same sad reality on either side of the war for those at home. However the human dimension expands beyond borders and patriotism, and it is this dimension which all humans share and that connects us with everyone else.

“No one has yet explained how war prevents war. Nor has anyone been able to explain away the fact that war begets conditions that beget further war.” (D.D. Eisenhower)

*1) Cameron, Alfred Edward, 1894-1967. Cameron sailed from New Zealand to Egypt with the Main Body of the NZEF in Oct 1914 and served as a trumpeter with the Canterbury Mounted Rifles. On 12 May 1915 he landed at Gallipoli where he saw action against the Turks. Soon afterwards he was discharged as medically unfit for service, and was shipped back to New Zealand.