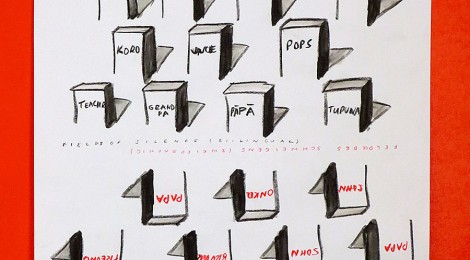

Fields of Silence (bi-lingual)

“The event stopped being about numbers and dates, and that the horrors of war; how it destroyed lives, families and how it did this with indifference to race, religion, nationality or the motivation for being there, became clearer to me.”

TOLGA ÖRNEK: (about working on his documentary “Gallipoli, the front line experience”, 2005)

Fields of Silence (bi-lingual)

coloured pencil and ink wash sketch on paper

2014 Daniel M. Kirsch

This work offers the perspective of both the German as well as the New Zealand soldiers (and their family members) who were involved in military conflict during the first World War. It can be hung in two ways, depending on the viewer’s nationality or choice of perspective.

The nearing centenary of the beginning of the First World War has led to increased coverage in the media with the result of a refreshed public awareness of the past conflict. War and a country’s involvement are often used to foster nationalism. Stories of undoubted heroism and self-sacrifice were cynically shaped into legendary proportions and used to bolster nationalist sentiment. What we fail to acknowledge is that this happens on both sides of the former opposing forces. The so-called enemies have their own view which often isn’t actually all that different– the words “enemy” and “us” simply need to be exchanged.

After a century the relationship of the involved countries has changed dramatically, and the current generations have little connection with the past. The view of enemies is no longer relevant. Generally in New Zealand we can observe a widespread readiness for remembrance of the war, as this offers an opportunity – albeit shallow – for an attempt of defining national identity. However this is mostly observed with the lack of questioning the true impact on the lives of individuals involved in the front lines. Neither does it include the so-called enemies and their families and close ones.

Rather than use the memory of past military involvement to foster national identity or even raise nationalist fervour and at times to support new military adventures, a more inclusive view of the actual impact and meaning of war is required. It is time to define our national identity on things beyond the bonding of going to war.